Rails to the Rescue: WW II Troop Trains Transport Millions of War Personnel

Published: 2016-11-02 - By: Jenna

Last updated on: 2022-02-07

Last updated on: 2022-02-07

visibility: Public

During World War II, the U.S. government relied on America’s extensive railway system to move the millions of enlisted personnel (close to 44 million armed services personnel traveled via U.S. railroads from December 1942 to June 1945) across the country to and from various bases and assignments. This form of transportation was the most practical given the gasoline rationing, the lack of an interstate highway system and only a few readily available passenger air crafts.

Although pragmatic, this mode of transportation did not come without its challenges. In December 1941, when the U.S. entered the war after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, the number of existing standard railway passenger cars was not nearly enough to haul the huge numbers of personnel and materials needed to support the war effort. As a result, the U.S. Office of Defense Transportation (created to ensure that all national transportation priorities were fulfilled), requisitioned the Pullman-Standard Car Manufacturing Company and the American Car & Foundry to build hybrid troop cars.

The Pullman-Standard Car Manufacturing Company produced 2,400 troop sleepers (a mobile barracks) and 10 kitchen cars, while American Car & Foundry built 440 kitchen cars and 200 hospital cars. These trains were vital to the country’s war effort. For instance, in 1944, considered the peak war year, 97% of military passengers traveled by rail.

In effort to create as many troop cars as quickly and efficiently as possible, these rolling stock were manufactured based on standard Association of American Railroads 50’ 6” single–sheathed steel boxcars. Made entirely of steel, with heavily reinforced ends, troop cars utilized existing design elements, fixtures, manufacturing lines, materials and production equipment. They featured the following: Allied Full Cushion high-speed swing motion trucks, light-weight passenger car-like flat ends and doors, freight car-like floors, roofs, and sides, a row of windows, and a centered door along each body side.

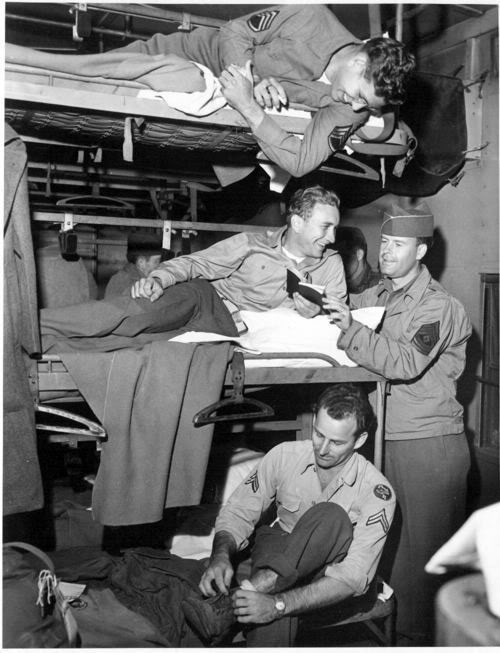

Troop sleeper cars were painted olive drab with "Pullman" lettered in gold above the center door. Although owned by the government, troop sleepers were managed by Pullman and staffed with company-employed Pullman Porters. Each sleeper could accommodate 29 military personnel (with bunk beds stacked 3-high) and a Pullman porter.

Staffed by U.S. Army cooks, troop kitchens or rolling galleys were usually positioned in the middle of the train so food could be served from both ends and designed to feed approximately 250 passengers each.

Depending on car availability, a typical troop train consist was made up of an assortment of coaches, troop sleepers for enlisted men, standard full-sized Pullmans for officers, and mid-consist kitchens.

Getting Home

Troop cars transported an impressive number of military passengers. The biggest troop movement of the entire war occurred on August 3-4, 1945, when Army returnees traveled from Camp Kilmer, New Jersey to different cities around the country. Some 20,000 soldiers packed onto 31 trains, requiring 331 Pullmans, 100 coaches, and 41 kitchen cars. That same week, more than 250,000 servicemen and women were transported in organized troop movements requiring 726 Pullman cars and 512 coaches.

Post War

After the War, the U.S. Army Transportation Corps sold the bulk of its lightly used fleet of troop cars (in service through 1947) to railroad companies, who ended up converting some of their acquisitions into baggage cars, cabooses, express service boxcars, mail storage cars, or refrigerator cars.

Used as railroad Maintenance of Way bunk cars for maintenance workers, some of the military surplus troop sleepers retained their sleeper configurations.

Carrying USAX reporting marks and road numbers with a "G" prefix, three of Pullman's troop kitchens were converted at Fort Holabird, in Baltimore, Maryland, to railway guard cars, which were used to house security detachments assigned to watch over rail shipments of classified cargo (e.g., missiles, nuclear materials, and/or military ordnance).